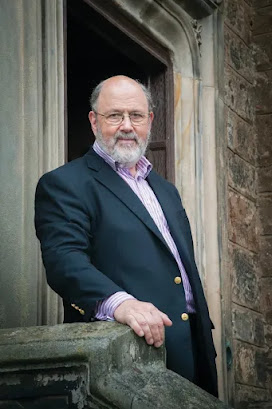

New Testament scholar and retired Anglican bishop N.T. "Tom" Wright, 69, has a new book, Paul: A Biography, which aims to help readers wrestling with the words of the Apostle by highlighting his distinctly Jewish roots.

When Christians engage in the life and writing of the Apostle Paul, their assumptions and conclusions are all too often misplaced.

But that is because the man best known for his lofty epistles to churches in Rome, Greece, and Asia Minor has been divorced from his Jewish heritage and way of thinking over the centuries of Gentile Christianity.

Paul never abandoned his Jewishness even as his ministry mostly occurred among Gentile believers, Wright argues; choosing to ignore or erase the Jewish significance to Paul's words is to disregard something profoundly important, rendering portions of the Scripture only partially understandable.

Wright's previous scholarship on Paul's theology and writing include Paul and the Faithfulness of God (2013), Paul: In Fresh Perspective (2009), and The Climax of the Covenant: Christ and the Law in Pauline Theology (1991/1992).

But biographers ask different sorts of questions, Wright notes in the preface, inquiries that search for "the man behind the texts." Substantive yet accessible, Paul provides a 432-page exploration of the Apostle's beginnings, his missionary journeys, his struggles and passion, and much more.

Below is a lightly edited transcript of The Christian Post's interview with the esteemed theologian and Pauline scholar.

CP: In all your years of biblical scholarship, ministry, and in the research and writing of this biography, what have you found to be the most common misconception among Christians and non-Christians about this man, Paul, whom the Holy Spirit inspired to deliver so much counsel to His Church?

TW: The most common misconception is that Paul was arrogant, muddled, misogynistic, and so on. Whenever people find something he says either difficult to understand (see below!) or too demanding on belief or behavior, the usual response is 'Oh, he just had a bad day when he wrote that bit' ... whereas in my long experience a little more thought and work on the passage usually reveals unsuspected depths and powerful meaning.

CP: The Apostle Peter famously wrote that Paul's letters contain things that are hard to understand and are distorted by ignorant and unstable people (2 Peter 3:16). Yet many sincere Christians also have a difficult time comprehending the words of Paul and would identify with Peter, as Paul's writings are often the subject of intense, vigorous debate about what exactly he is saying. Why has he been and still is so misunderstood?

TW: Paul's writings are dense. He was writing often in difficult circumstances (in prison, on journeys, etc.) and often didn't have a chance to correct let alone expand what he was saying. In particular, he was trying to tease his readers/hearers into thinking for themselves, not simply accepting pre-packaged formulae without reflection.

But this means that, like many poets and other artists, he has to risk leaving questions open (though he's pretty clear on a lot of things!). In particular, because he knows his Bible inside out he can assume that his hearers can follow him when he's stringing together ideas that for their full meaning demand a ready grasp of the larger contexts of the passages in question. And he was writing within the complexities of the larger Greco-Roman world in which the swirling philosophies of the time meant that the same sentence could easily be interpreted in different ways, particularly by people who didn't know Paul personally ...

CP: It could be argued that Paul's life constitutes one of the greatest if not the greatest redemptive stories in all of Scripture. A man who once murderously opposed the followers of the Way encounters Jesus, is blinded en route to Damascus, and is in the years that followed used by God powerfully and pens approximately 1/3 of the New Testament. What did it mean for him to exchange such zeal to do evil for zeal for the Gospel and the surpassing greatness of knowing Christ (Philippians 3:8)?

TW: It was of course a total turn-around from one point of view; but, from another, Paul firmly believed he was still following the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob as he had throughout his life. There are parallels: Moses had killed the Egyptian and had to run away, but God called him to a new task; Elijah killed the prophets of Baal and then had to run away and God recommissioned him . . . But in Paul's case what it all meant was, of course, that Jesus of Nazareth really was Israel's Messiah, designated as such through his resurrection, and that he really had inaugurated the new world for which he (and all Israel) had longed – even though it didn't look like Paul had imagined previously.

If this sounds confusing to us, it was no doubt deeply shocking for Paul himself, which is why it took time – not least his trip to Mount Sinai in Arabia, like Elijah! – to get his head and his heart around it all. And then the ten 'silent' years back home in Tarsus after his early efforts to persuade people of the truth of the gospel ... that must have been a hugely demanding time, but all we later know of Paul indicates that he used it to go deeper and deeper in prayer and scriptural understanding which would then bear such fruit in his remarkable traveling work.

CP: In your book, you maintain that scholars and pastors have not sufficiently considered the "human side" of Paul. How and why have they failed to do this?

TW: When you treat Paul's letters as 'holy scripture' (as I personally have always done) it is very tempting to think of them as simply 'words from above,' not also 'the words of a human being, often drawn out of him through suffering...' But it's only when we examine the real human situations in which Paul found himself, particularly his imprisonments and often terrible circumstances, that we really understand what he was talking about.

He saw himself as a walking illustration or example of the truth of the gospel of the crucified Messiah. To understand that, we need to look long and hard at his human side. That is where we then discern the true word of God in his human words.

CP: You stress that although the main focus of Paul's ministry was to the Gentiles, Paul cannot be separated from his Jewishness, that his life and work can only be understood in the context of the Jewish world in which he once lived. Why is grasping that vital to understanding his subsequent endeavors in Rome and elsewhere?

TW: Paul never stopped thinking, speaking, and writing as a Jew – a Jew who believed that the One God had sent the true Messiah. Generations of Gentile Christianity have often tried to ignore or even erase that Jewish meaning, turning 'Christianity' into an essentially non-Jewish system and making most of Paul's major themes only semi-comprehensible.

Paul's message for the Gentile world was precise that Israel's God had defeated the idols worshiped by the pagans and had launched a new way of being human in which the scriptures had all come true in a new way. Non-Jewish groups from the second century onwards have always tried to flatten this message out into a 'new way of being religious' or of 'being saved' – a way which could then be played off against the world of ancient Israel and its scriptures. But every step in that direction is a step away from Paul.

CP: You also trace the Apostle through his missionary journeys, noting his perseverance through being shipwrecked, jailed, and nearly killed several times. Why is what he accomplished so extraordinary in light of the fervent opposition he endured?

TW: Paul's accomplishments rank him as among the greatest public intellectuals of all time – up there with Plato or Cicero. Yet they lived privileged lives – albeit in a dangerous world – and Paul was always on the move, only able to write short, tight-packed letters, not leisurely treatises and dialogues. His utter self-giving to his communities, and his modeling of the new way of life he was commending, was more powerful still, as people realized that there was indeed a new way of being human launched upon the world and this is what it looked like.

That's why when Paul told them that he was imitating the Messiah so they should imitate him they started to do just that ... and the rest is (church) history.

CP: It's rather remarkable that your book has come out around the same time as the movie Paul: Apostle of Christ. Have you seen it, and if so, what did you think?

TW: I haven't seen the movie ... but yes, it's interesting as a coincidence. I suspect it will find it hard to condense what needs to be said into the normal time-frame for a movie. I would rather make a series of television programs ... but that's another story.

CP: It sure seems that many Christians in the West are now struggling to find a language with which to engage culture, not only because of the proliferation of digital technology but, as you mentioned in a London Times editorial last August, a resurgent Gnosticism overhauling once thought obvious definitions of things like 'male' and 'female,' which yields confusion about "the ultimate reality of the natural world." Yet these present challenges, while profound, are really not so new. As you document extensively in your biography of Paul, the Apostle faced all kinds of issues relating to the Gentile and pagan people groups among whom he ministered during his travels. He had to change his language radically (perhaps most famously when he addressed the Athenians in Acts 17) in order to communicate the Gospel message effectively. How might Christians take a page from Paul and learn to speak to an increasingly hostile, secular society that does not understand them?

TW: The Acts speech was a legal defense against the charge of 'introducing foreign divinities' – part of the accusation that had condemned Socrates. The 'Areopagus' was not a debating society; it was the highest court in the land. Paul's speech to the court was not a 'change of language'; it was addressing a different set of questions. His message was always about the one true God and his purposes, over against the pagan gods (see 1 Thessalonians 1, probably written at the same time when he was in Athens), and this is what comes across in the speech.

However, the point is important: Paul declares in 2 Corinthians 10 that he 'takes every thought captive to obey the Messiah', and it is vital that Christians in every generation learn to do the same, in particular (as Paul insists) to discern what matters, to distinguish things that differ, to be wise as serpents and innocent as doves.

The message of the crucified and risen Messiah is of course not 'comprehensible' in terms of anyone's worldview – but as Paul discovered it possesses a strange power to go to the heart of things and to transform human beings and societies with the presence and power of the living God.

CP: How has writing a biography on Paul deepened your own faith?

TW: It has helped me to see myself as living within the long and often complex and troubling story of how the Jesus-movement makes its way in the world.

It has reminded me that being faithful to Jesus doesn't mean being 'successful' in the world's eyes, nor being free from pain and trouble; but that it will produce, again and again, a joy that transcends all of that.

No comments:

Post a Comment